David A

Last night is the worst in recent memory. I crash asleep with a ripping headache around 8pm, but wake only two hours later. The snoring of one of the other climbers in the room is unfathomable — loud, erratic, beastly and inhuman. Subsonic waves accompany the audible abominations, causing deep internal vibrations and nausea, and, if near an ocean, disorienting any whales within 50 miles.

I toss for a couple of hours, which flopping is only interrupted by periodic need to recycle my herbal tea — which means a cold crawl out of my sleeping bag down two flights to the rancid one-stall bathroom, immediately next to a door to the frigid outside that is never closed (reflecting a judgment, that is unassailable having experienced these two evils of cold and stink, that cold ventilation is better than no ventilation). A first night at over 15k hits me hard, just as Ossy predicts. After wallowing a bit more, maybe around 2am, I get up for more Advil and ear plugs. The latter actually help, but I then discover a new hell: apoxic apnea. Now plugged off from the terrifying din of a neighbor’s guttural thunder, I am finally able to nod off. But every time I start to drift, I jolt awake, gasping, convinced I am suffocating. Horrible stuff. I get maybe three hours of sleep and a fresh headache by the morning.

David A

At 7:30am I force myself downstairs, to a gorgeous sunny day that beams warmth and hope into the dining room. I drink three cups of coca tea, add another dose of Advil, and pop my first Diamox. Within an hour, I ‘m improving. By the time the glacier school bell rings, I feel nearly normal.

A Belgian woman sits nearby with her Ecuadorian guide. Ossy tells us they attempted a summit last night — in what looked like perfect conditions — but turned back at the glacier after hearing loud, ominous cracking caused by a condition Ecuadorians call superficial tension. Temperature differentials create unstable fractures, which in a worst case can trigger ice avalanches. They had no choice but to retreat a few hours into their attempt.

We start with indoor work: knots and belay techniques. We practice the overhand figure-eight, the clove hitch, the munter hitch, and various bight knots. We cut prusik cords to length and build prusik systems off an overhead anchor in the hut.

Courtesy Carl C

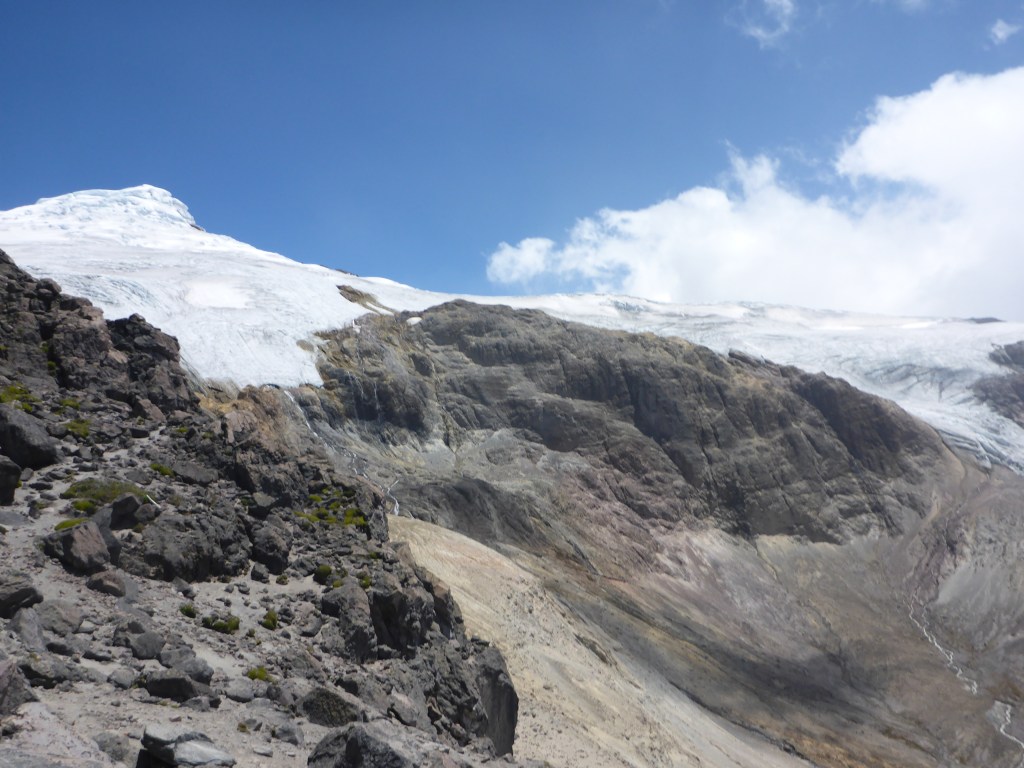

Then we head outside into weather that is mostly beautiful — warm, sunny, with the occasional mist. We rappel using a prusik backup and ATC belay system. It’s excellent fun: beautiful views, minimal exposure. We each do three different rappels before breaking for a lunch of potato–cilantro soup.

Courtesy Ossy F

After lunch we return to the rock to practice crevasse self-rescue using only a two-prusik system: one prusik attached to your harness, one to a foot loop. By alternating weight — slide foot prusik up while sitting back, then stand to slide the harness prusik — you can, slowly and with heroic effort, ratchet yourself up a fixed rope. Overhangs are brutal: the top prusik is pinned by your own weight and must be slid past a kink in the rope. At one such point, I simply abandon the foot prusik and free-climb while inching the top prusik upward to “bank” progress..

Next, we go just downhill from the refuge to practice rope-pulley rescue systems. A few of us are tired, and the instructions are coming at us fast, so tensions become more than superficial. One climber has enough and just opts out of the pulley class. I enjoy this session too, but doubt I will remember enough to even approximate these techniques if needed. I reassure Jeff that instead I will just keep practicing cutting our rope.

Alex and Carlos head back down to the lower hut again, but the rest of us are in for another night at the crappy upper refuge. (By any objective standard, the upper hut is perfectly adequate — palatial, even, compared to tent camping — but objective standards don’t make me feel better, so you get this exaggerated, contorted perspective.) I’m hoping for some sleep.

Originally we planned to stay here a third night, but I orchestrate a revolt, and Ossy now blesses our descent to the lower hut for both Saturday and Sunday nights. Otherwise Saturday (as the busiest climbing day) will involve — spellcheck just changed that last word to “violence” — a climber into every single bunk of this small lodge: triple-level beds crammed so tightly you couldn’t even lose a sock between them. Add a mass of tangled climbing gear and the scene becomes uninhabitable. Compare that to the lower lodge — showers, laundry, real meals, and the place entirely to ourselves — and you can see why the coup succeeded.

Tomorrow will be a hard day. We head to the high glacier for a full day of ice training. Friday night will bring more climbers, including a group of eight Germans and their four Ecuadorian guides. Dinner tonight is fish and rice. The fish is tasty, but I’m too tired to do the work of picking bones. Carl finds a different solution: he simply crunches up the bones and eats everything.

David A